Starflate: Deflate decompression in C++23

In this post I describe some things I learned while working on Starflate, an implementation of Deflate decompression in C++23 that I wrote with my friend Oliver Lee.

Deflate is a compression codec used in GZip, Zip, PNG and other formats. I wanted to get hands-on with GPU programming and I decided implementing Deflate decompression would be a fun way to do that. After finishing the CPU-only implementation, I realized that there is no way to efficiently parallelize it, so I will have to find something else to use to learn GPU programming. But along the way I did learn quite a bit about compression and C++.

Deflate decompression

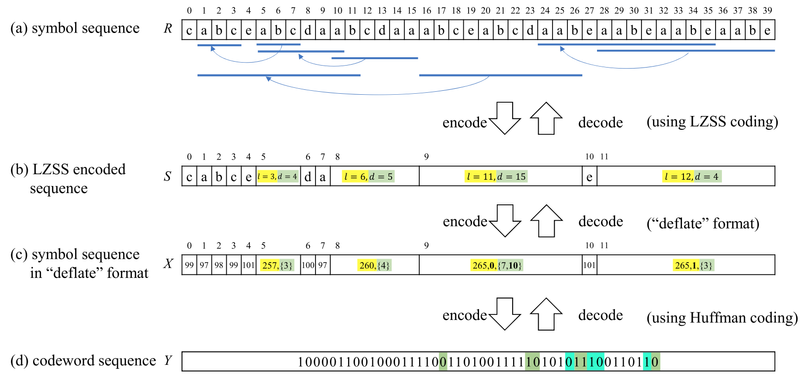

I think this diagram does a pretty good job of showing the different layers in the Deflate compression algorithm:

Figure 4 from Takafuji et. al, 2022

The innermost layer is LZSS, in which the input is a series of either:

- A “literal”, meaning just copy this byte to the output, or

- A length and backwards-distance pair (l, d), meaning copy l bytes starting from output[-d] to output.

The second layer is an encoding scheme for the length and distance pairs that doesn’t seem to have a name, but is shown in the diagam as “deflate” format. The deflate standard defines a code table for distances and another for lengths. This steps to decode goes something like:

- Look up the code in the table. This gives a base value and a number of extra bits to read from the input.

- Read those extra bits from the input, interpret them as an integer.

- Add the integer to the base value.

The outermost layer is Huffman coding. I won’t do a better job than Wikipedia of explaining it, but basically it’s a provably optimal (as in maximally compact) prefix-free coding scheme (meaning the code for any symbol is not a prefix of the code for any other symbol).

Finally, there is the added complexity that the Huffman code tables themselves can be included in the compressed data, and they are encoded using a scheme similar to the second-layer (“deflate” coding) scheme (but slightly different).

Starflate design

The core implementation of decompression is 391 lines of code (excluding comments and blank lines), and I think it’s relatively readable. However, there are another ~1300 lines of code in helper libraries we wrote for dealing with bit streams and Huffman coding. These helper libraries allowed the main code to stay quite short and readable.

bit_span

bit_span is like std::span in that it is a non-owning view of a contiguous extent of the same type of data. Unlike span, bit_span allows its users to iterate over individual bits, even though the underlying data is stored as bytes.

huffman::table

huffman::table is a Huffman code table. For ease of testing it has a bunch of different constructors, but the only one used in decompression is the one that takes a range of pairs of (symbol range, bitsize). Huffman coding uses prefix-free codes, meaning that we decode the input one bit at a time and we’re done as soon as we find the bit pattern in the table. Internally the table stores things sorted lexicographically, which allows for efficient decoding by keeping track of where we are in the table in between attempts to decode the bits. In an attempt to be idiomatic C++, the table exposes iterators with the standard begin() and end() methods. The main use of the table class is in decode_one, the pseudo-code for which is:

def decode_one(huffman_table, bits):

table_pos = huffman_table.begin() # iterator

current_code = 0

for bit in bits:

current_code = (current_code << 1) | bit

std::expected<table::iterator, table::iterator> found = huffman_table.find(

current_code, table_pos)

if found:

return found->symbol

table_pos = found.error() # uses expected::error to hold the next iterator position

if table_pos == huffman_table.end():

return error()

return error()

C++ features / patterns

A few C++ features or patterns I learned along the way. Thanks to Oliver for teaching me all these (and more that didn’t stick!).

constexpr

My biggest C++ lesson learned is that a large fraction of the language and library features are compatible with constexpr, meaning they can be evaluated at compile time. While there are potential runtime performance benefits to this, it’s also cool that this guarantees the code contains no undefined behavior. That is, this is a way to convert potential runtime errors into compile-time errors. This is the one feature of C++ that I actually missed when writing Rust recently.

std::expected

Added in C++23, std::expected contains either an expected or an error value. It’s a sane way of propagating errors and we used it extensively. This is one of those things that I didn’t notice was missing from the language when I worked at Google because Google had its own version. Actually the standard library version is better because both the expected and error types can be templated, which we took advantage of for huffman::table::find’s return type.

The overload pattern: pattern matching

You can combine std::variant, std::visit, and the overload pattern to get something like Rust’s pattern matching. We used this here to dispatch to different code paths depending on wheter we decoded a literal byte to be copied to the output, or length of previous output to be copied. The syntax for it is terrible though. This example from C++ Stories is a good one:

template<class... Ts> struct overload : Ts... { using Ts::operator()...; };

std::variant<int, float, std::string> intFloatString { "Hello" };

std::visit(overload {

[](const int& i) { std::cout << "int: " << i; },

[](const float& f) { std::cout << "float: " << f; },

[](const std::string& s) { std::cout << "string: " << s; }

},

intFloatString

);

Template deduction guide

A template deduction guide is some code that one can add to a templated function or class that tells the compiler how to fill in template arguments. This can make using the templated function or class much more readable.

This example from cppreference is a good one:

// declaration of the template

template<class T>

struct container

{

container(T t) {}

template<class Iter>

container(Iter beg, Iter end);

};

// additional deduction guide

template<class Iter>

container(Iter b, Iter e) -> container<typename std::iterator_traits<Iter>::value_type>;

// uses

container c(7); // OK: deduces T=int using an implicitly-generated guide

std::vector<double> v = {/* ... */};

auto d = container(v.begin(), v.end()); // OK: deduces T=double

Missing feature: iterator_interface

A lot of the standard library exposes and operates on iterators, so it’s nice to also do so when writing custom data structures. Quoting the proposal for adding std::iterator_interface: “Writing STL iterators is surprisingly hard. There are a lot of things that can subtly go wrong. It is also very tedious, which of course makes it error-prone.” We needed a couple of iterators (one for bit_span and one for huffman::table), so we added a simple version of the iterator_interface. There is an implementation in Boost, but we wanted to avoid any external dependencies.

Setting up C++ is horrible

C++ takes an insane amount of set-up to get a repository that has what are extremely easy in other languages. We set the following up, and none of it is really standard or easy to do:

- Build system. One has to choose between Make, CMake, Meson, Bazel, etc. We chose Bazel because it’s good and we’re used to it, but it takes a lot of work to set up, it’s poorly documented, and less common combinations of features (like C++ test coverage with Clang) have been broken.

- Hermetic toolchain, meaning inside the repo we define what versions of Clang, GCC, etc we want to use, rather than relying on whatever is installed on the system.

- Sanitizers. E.g. thread sanitizer, address sanitizer, undefined behavior sanitizer. These are compilation modes that instrument the code and fail if the code does something bad. Address sanitizer and undefined behavior sanitizer aren’t needed for most other languages, but I think it’s pretty insane to write C++ without them.

- Static analysis (AKA linting). Basically turn on all the compiler warnings and treat them as errors (pretty insane that this is not the default for most of the warnings), and also run clang-tidy. Running clang-tidy through bazel is not straightforward but Oliver figured it out.

- Autoformatting. Again insane that this is not the default, and one needs to do extra work to get it configured in editors and enforced in CI.

- Bringing in third party dependencies is horrible, and you need at least some third party dependencies because the standard library doesn’t include a unit test library.