Attention, Memory, and Productive Knowledge Work

Here I present some ideas for increasing the productivity of knowledge workers by structuring their workflows around attention and memory. I wrote this for my own benefit, but I hope you find it useful too!

Workflow matters

By “workflow” I mean loosely how execution tasks are scheduled and coordinated. By “execution tasks” I mean the activities which more-or-less-directly create value. For a software engineer, these tasks include programming and designing.

Much of the most influential thinking about optimizing workflows to increase productivity comes from the automobile industry. The history of car manufacturing has several inspiring examples. In 1909, a Ford Model T Runabout sold for $27,977 (in 2024 USD). In 1925 (16 years later), it sold for $4,517 (also in 2024 USD)1. The number of Model Ts you could buy per dollar increased by over 6x!

Much of this increasing productivity was due to changes in the workflow. One major change was the introduction of the moving assembly line. Prior to the assembly line, cars were built through “the craft method”, in which teams of fifteen workers worked simultaneously on a single car”2, which makes me think of young children playing soccer. This was inefficient in many ways. People got in each others’ ways, and they had to spend time walking around the factory to go between cars. With a moving assembly line, parts came to the workers and each worker could complete their stage of production without having to walk, coordinate with others, move tools, etc.

Attention and memory matter

In manufacturing, the main inputs wer materials, equipment and manual labor. In knowledge work, the main input is human minds. To increase productivity, we need to produce more output without increasing inputs. One way to do this is to optimize the workflow! One way to optimize the knowledge worker workflow is to understand some properties of attention and memory.

“Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity that can hold information temporarily.”3 It is essential for reasoning and decision making, which are crucial in knowledge work. The set of mental objects you can mentally manipulate at one time is limited by the capacity of your working memory. After switching tasks, it takes time to build up working memory.4

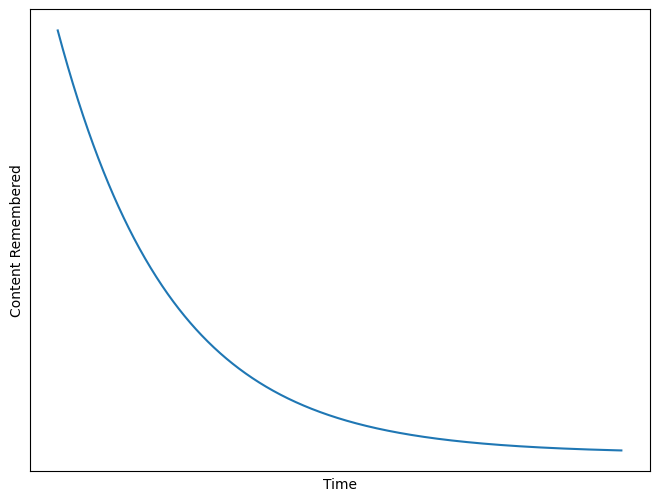

Long-term memory is the system that lets you restore previous working memories. “Forgetting” means something being lost from long-term memory. The “forgetting curve”5 is a stylized fact. The longer you go without retrieving a memory, the more likely you are to forget it.

This conceptualization of human memory is quite similar to how computers work: working memory is analogous to a computer’s volatile memory (e.g., registers), long-term memory is analogous to persistent storage (e.g., a flash drive), and forgetting is analogous to deleting a file.6

If it’s not obvious by now, workflow interacts with how our memories work. Every time one switches tasks, one must repopulate working memory before becoming productive. And extended periods between working on a task leads to forgetting. One must re-learn, which takes time.

Ways our workflow makes us less productive

Yet many knowledge workers switch tasks very often. This has obviously been the case in many places I’ve worked, but there is some objective data to support this impression: A report from the summer of 2018 analyzed data from over fifty thousand active users of the RescueTime time tracking software. It found that the median time between checking communication apps like email and Slack was 6 minutes, and more than 2/3 of the users never experienced an hour of uninterrupted time.7

Besides this short-term switching between execution and collaboration, people often switch between tasks that they are executing. On several projects I worked on it was common to have work items that went unfinished for months, with sporadic bouts of work spaced weeks apart. Work done this way has many costs, but it definitely incurs costs of forgetting and re-learning.

Suggestions

At a high level:

- Minimize context switches so as to avoid cost of loading things into working memory.

- Minimize time between sessions of work on a single task so as to avoid forgetting.

- Remember that convenience ≠ productivity.

And now some specific ways to put these principles into practice.

Use meetings well

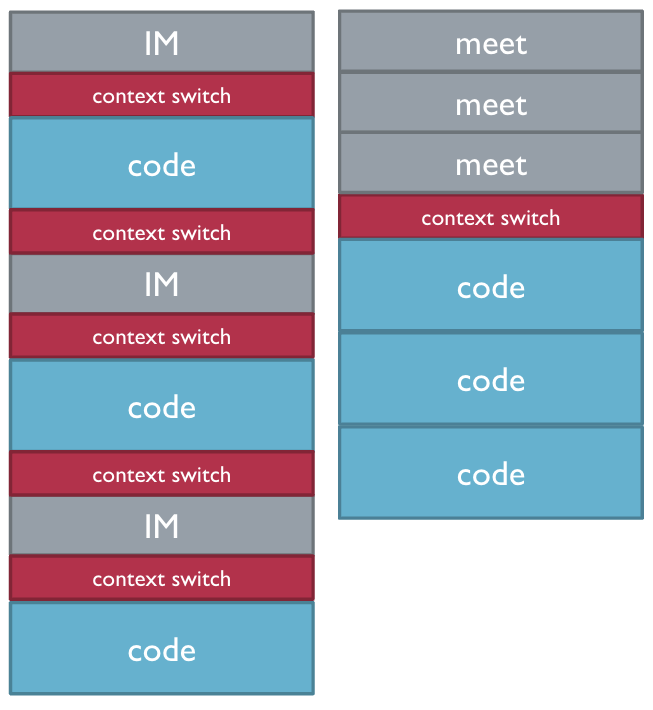

Instant messages, e-mail, and interactions on doc comments are all asynchronous. Each message involves a context switch. Meetings are synchronous, rapid, concentrated communication. My rule of thumb: after the third message in an E-Mail or IM conversation, it’s better to switch to a meeting. An illustration of the cost of context switches that can be avoided by a meeting:

Meetings certainly have their own costs, and are often run poorly, but producing fewer context switches is a huge and underappreciated advantage of meetings over asynchronous communication.

Meeting tips

Regularly scheduled meetings are useful for regular, non-urgent communication. Participants know they’ll be able to discuss things relatively soon, and therefore can avoid resorting to asynchronous communication. Between meetings, participants can collect agenda items in a document as they arise. This is an example of convenience ≠ productivity. If I think of something to ask my coworker, it’s more convenient for me to IM him. But, if it’s not urgent, it’s more productive for me to write it the agenda of our next regularly scheduled meeting.

For group meetings, it can be efficient to have a structured way for participants to schedule smaller-group follow-up meetings. When I was a manager at Microsoft, my team’s regular sync meetings were 60 minutes, but the whole team was only expected to meet for at most 30 minutes, and the rest of the hour was used for smaller group follow-up meetings. This avoids a context switch between blocks of meetings and blocks of solo wrk. And it avoids asynchronous back-and-forth to schedule a follow-up meeting.

Finally, there are many ways meetings can be inefficient, but if participants are vigilant and vocal, they can be improved (or cancelled! Not all meetings are worthwhile).

Schedule asynchronous communication

By default, don’t leave your inbox open, don’t leave your IM app open, and don’t leave your phone notifications on. Check these things on a schedule that balances responsiveness to others with your own ability to focus. Personally I follow a loose schedule of checking things first thing in the morning, immediately before meetings, and once or twice during the afternoon, when I happen to feel blocked or need a mental break.

I used to have a problem with getting distracted by my inbox every time I sent an email. To send email without checking your inbox, you can use this link for GMail or this one for Outlook.

Schedule focused work

One technique for avoiding self-imposed distraction is called “Pomodoro”, which basically consists of setting a timer, and taking a break when the timer goes off.

To increase the odds of having large blocks of time to focus, schedule events on your calendar that prevent others from scheduling meetings. If you have the option to work in a place that is quiet and physically isolated, try to do that during your scheduled focus blocks.

Limit the number of in-progress tasks

Limiting the number of tasks that you have in-progress can help reduce the temptation to context switch (and flush your working memory) and it will reduce the odds that you forget important details about one incomplete task while you’re working on another. This is a key feature of Kanban and Scrum.

Use tools to disseminate commonly needed information

Some information is so commonly needed that the questions should be anticipated and built into tools that are used as part of the regular workflow. For example “Who is working on this task?” Proper use of an issue tracker (e.g., GitHub Issues, Asana) can answer this without the back-and-forth of asynchronous communication or the time burden of a meeting. If you find there is some question like this that is repeatedly asked, but has fairly formulaic answers, check if there’s a tool that you can adopt that will disseminate that information more efficiently.

Speed up testing and reviews

This is somewhat specific to software development, but it probably has analogs in other professions.

The “testing and reviews” part of the software workflow typically looks like:

While not approved:

Author: rebase, (read / think, write, build, run) until ready.

Wait for automatic checks.

Reviewer: read / think, comment. Maybe approve.

This leaves plenty of room for context switching and forgetting:

While not approved:

Wait for author to start. Author and reviewer forget.

Author: rebase, (read / think, write, build, run) until ready. Author context switch. Reviewer forgets.

Wait for max(automatic checks, reviewer to start). Author and reviewer context switch + forget.

Reviewer: read / think, comment. Maybe approve. Reviewer context switch. Author forgets.

What can we do about this? If automatic checks are frequently the bottleneck, spend time speeding them up. If code reviews are the bottleneck, speed those up. On a previous team I set up a duty rotation to review any changes that did not yet have a reviewer. You might also experiment with pair programming, which basically combines code review and programming.

Acknowledgements and further reading

Besides my own experience, this post is based on the following:

A World Without Email by Cal Newport.

Deep Work by Cal Newport.

Getting Things Done by David Allen.

More Effective Agile by Steve McConnell.